Can Gender Wage Gap Destroy Democracy?

Executive Summary

Shrinking gender wage gap is a key stepping stone for a country that aims to be democratic, and therefore, diverse and inclusive. Gender equality is significantly interrelated with a nation’s peace, its domestic security, and its levels of hostility toward other states (Piccone). become the targets of racist and sexist behavior, then inequality must be addressed. Pay disparity is quite obviously anti-democratic since it significantly reduces prospects for growth by subjecting people to the racist and sexist abuse, diminishing their access to education, health care, job opportunities, all of which further weakens the voices and votes of those who are radically, shamelessly, and structurally underpaid.

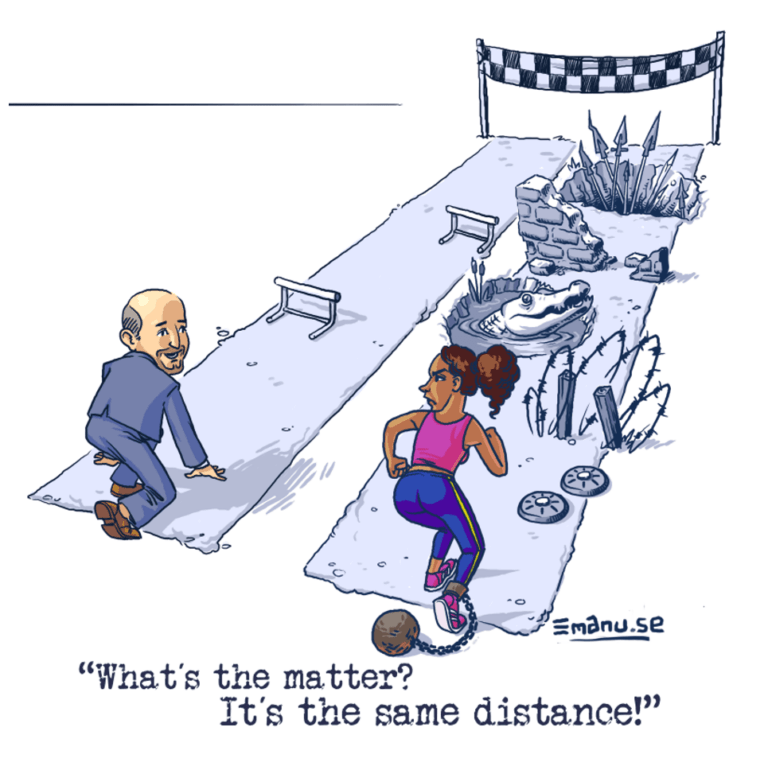

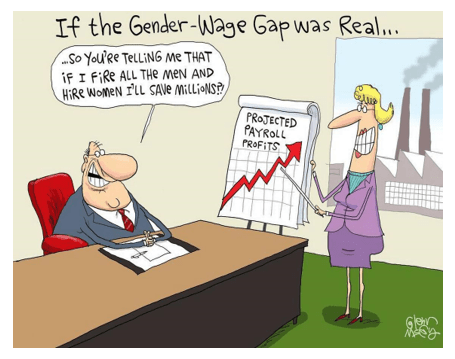

Fig: Gender-Wage Gap: debunking the myth

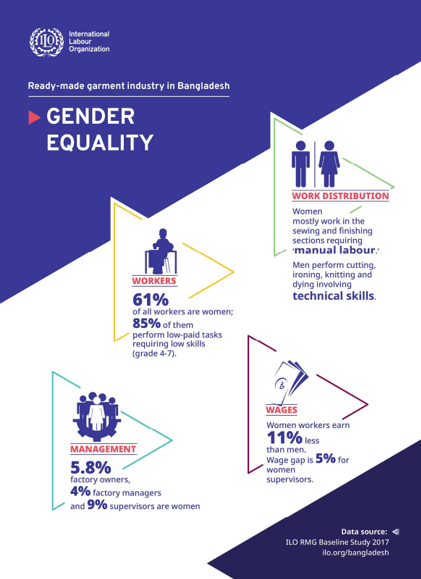

So, strategies to improve democracy should prioritize women’s empowerment, holding perpetrators of violence against women and girls accountable, and eliminating the gender gap in politics and the workplace. Despite Bangladesh’s immense and astonishing progress in economic development and women’s empowerment, men still earn hourly wages 57% higher than women (Shibli).

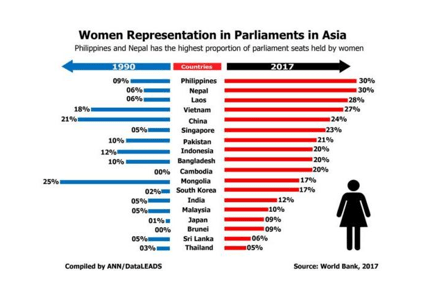

Fig: Women Representation in Parliaments in Asia

From 1990 to 2017, women representation in Bangladesh’s parliament has only doubled (World Bank, 2017). On this front, there is still much progress to be made. Equal pay is blueprinted to elevate gender equality, which reinforces democratic institutions like government ministries, elected bodies, political parties, and civil society organizations, according to research and real-world experience (Piccone). Globally, people view female legislators as being more trustworthy and approachable than their male counterparts (Van Den Akker et al. 13). As it is widely accepted that men hold superior positions in the parliament and therefore receive higher pay, women are often relegated to subpar levels of politics. It is important to note that logistic regressions revealed that those with greater salaries had higher rates of civic engagement (knowledge about politics, striving to improve women’s welfare in the community, etc.), whereas those making less than the minimum wage had lower rates. (Levin-Waldman).

When democracy is deliberately delegated, it should mean that everyone has fair opportunities and adequate income at their disposal to afford necessary goods. They should be able to maintain a standard of living that allows them to secure good jobs, higher education, quality healthcare, shelter and so on. It has been found that if Italy’s equal distribution of women across wage rates is used, the gender wage gap is predicted to decline rapidly in social democratic countries (Mandel & Shalev 14).

Traditional gender norms have an impact on pay inequality as it determines how a society values or devalues a specific gender’s role in their respective jobs. For example, there is a longstanding view that women have to juggle household chores, profession, care work, etc. (Carmichael). In order to ensure that no gender falls behind while climbing the career ladder, it is imperative to eliminate these patriarchal notions. Sometimes, the additional household responsibilities result in less professional productivity, less possibilities for career growth, and lower pay than their male counterparts.

Moreover, there are not many trustworthy or cooperative child care institutions in Bangladesh. Similarly, when a woman or third gender faces harassment in the workplace, it’s likely that person will not rejoin the workforce or be compensated. Labor laws such as employment injury protection exists but not all companies abide by it.

Current State of Female Representation

Conventional wisdom holds that democratic regimes tend to improve gender equality by expanding civic space for women’s activism, increasing women’s participation in politics through voting and/or removing unfair restrictions on their ability to participate in politics. On the other hand, gender equality is viewed as a key factor in democratization since it increases the economic and political power of a larger segment of society.

The mutually reinforcing process between democracy and gender equality is likely not possible in countries with lower or moderate levels of democratic quality since they do not offer enough civic space or opportunities for engagement, e.g. Kazakhstan and Rwanda compared to Yemen and Pakistan (Piccone).

The good news is that there are several organizations in Bangladesh that work towards promoting gender equality. The grassroots labor rights NGO “Awaj Foundation” works towards enabling positive workplace relations and empowering workers. They put female leadership at the forefront of their projects and services. Their main goal is to give workers the voice to demand decent working conditions, especially in the garment industry. Overseas, Google and Norway’s largest bank DNB actively address issues that put women at a disadvantage compared to men (Nandi et al. 434).

Google and Accenture improved their paid parental leave policy which significantly helped close the gender pay gap. One of DNB’s important policies is to not treat pregnant female employees less favorably. In addition to providing a paid parental leave to its staff, DNB has also implemented extra compensation for them. These kinds of modifications assist in making up for the generally lower income of women on maternity leave. Other than the private sector, the government and the wider economy should also tap into the underlying drawbacks of the country’s democratic system which can solve many issues in one fell swoop.

To remedy the shortcomings, appropriate strategies and a mindset change are required. Bangladesh has made significant strides to achieve women’s emancipation. However, women still need to be elevated from local to national and international levels. A comprehensive anti-discrimination approach, starting with addressing the wage gap issues, can go a long way. Gender equality needs to be integrated at every level of policy-making and implementation of it.

Fig: Gender Inequality in RMG industry in Bangladesh

Secondly, states should implement measures to guarantee that all women have an equal opportunity to serve in national legislatures, including giving female candidates preference in order to correct imbalances and focusing support and protection on female candidates and legislators, particularly in nations where women are underrepresented in political parties. Historically, women are significantly underrepresented in democratic institutions and positions of power (Markham & Foster). Institutions are frequently set up and run in a way that, unfortunately, promotes the agendas of male incumbents rather than the interests of its members. Enabling female diplomats to engage in high-level decision making, especially when it comes to judicial and security sector reform, is the way forward. The government ought to promote legislation that guarantees women’s full involvement in politics and lawmaking at all levels, from neighborhood councils to cabinet seats. The Ministry of Women And Child Affairs could initiate programmes which address the social, cultural and economic barriers that limit young women’s political participation and ensure that these reach the young women in the rural areas too. The programmes can give them a platform to voice their opinions and network with other aspirants and female Members of Parliament.

Thirdly, investing in child care programs and daycare centers can welcome a much-needed structural change in Bangladesh to overthrow the age-old gender stereotypes that women are meant for unpaid care work. Higher levels of equality and security have been attained as a result of the declaration of safe havens with enforceable protection provisions where women can pursue economic activities free from harassment. In the development of gender inequalities in jobs throughout the course of a person’s life, having children is a critical turning point. The percentage of women working drops steeply from 90% to 75%, and the average number of hours worked each week for those who are still employed drops from 40 to under 30 (Nuffield Foundation, 2021). This is pivotal to understanding the gender wage gap since it also marks the beginning of a prolonged phase during which women’s hourly wages stagnate, in part because working fewer hours tends to halt rise in wages. The paths of employment, hours, pay, and earnings for males are, in the meantime, substantially unbroken by childbearing. Therefore, states should vigorously support policy initiatives aimed at reducing the wage gap between men and women, including paid parental leave and child care.

Lastly, increasing pay transparency holds employers responsible for any discriminations regarding salaries. The government can create incentives for companies that can justify any differences in wage, protect workers from those who share pay information, and compensate victims of wage discrimination. Women presently earn $0.80 for every $1 earned by males (Wilson). With pay transparency enforced, women are still paid $0.98 to every $1 earned by males for the same job. While the average difference of $0.02 may not seem like much, it is statistically significant, especially in light of the fact that pay discrimination has been prohibited since 1964.

Conclusion

Liberal democracies place a strong emphasis on free and open competition between equals in the public arena, but they pay little attention to how private power affects women’s political voice and their ability to compete on an equal footing with males. Women have little prospect of genuinely challenging the underpinnings of males’ social and political supremacy without constitutionally sanctioned compensation for these restrictions on their political participation. Strategies to strengthen democracy and human rights should place a focus on women’s empowerment, holding perpetrators of violence against women and girls accountable, and eliminating the gender gap in politics and the workplace. Moreover, advocates for gender equality frequently lack the strength to successfully influence policy or compel states to prioritize the power abuses that concern women the most. In order to ensure political participation chances and resilience against gender-based violence, economic empowerment of women is essential. At sectoral or workplace level, enacting and enforcing equal pay and anti-discrimination laws is necessary to create a framework for assuring equal compensation for work of equal value and to give victims of pay discrimination access to the legal system. It creates a conducive environment for gender mainstreaming in developmental issues, institutions, civil spheres and economic structures. Thus, the wheels of democracy cannot turn without every individual experiencing a basic level of autonomy which comes with eradicating the discrimination in pay.